When Hasan Hujairi was a graduate student in South Korea, his friends took him to see a fortune teller. But instead of reading his future, the fortune teller said she felt compelled to tell him about one of his past lives. She told him that he had been a (Korean) monk who had spent his whole life in the monastery, only to eventually leave it behind to explore the world in search of truth.

Now, some 40 years into his current lifetime, Hujairi continues to explore the world seeking deeper understanding and connections between people. Born in Bahrain, he studied finance at Drake University in Des Moines Iowa, earned a master’s degree in economics with a focus on maritime historiography from Hitotsubashi University (Tokyo, Japan), completed a doctorate in music composition at Seoul National University in Seoul, South Korea and, since January 2023, he now leads the music department of the non-profit Sharjah Art Foundation in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates.

We asked Hasan some questions about his music, his multidisciplinary education, and his plans for the future of the Sharjah Art Foundation and for his own artistic work:

Eighth Nerve (EN): With the notable exception of Iowa, everywhere you’ve lived has been either an island, a peninsula, or coastal. Do you think that living on an island or in proximity to the sea has an effect on your way of thinking?

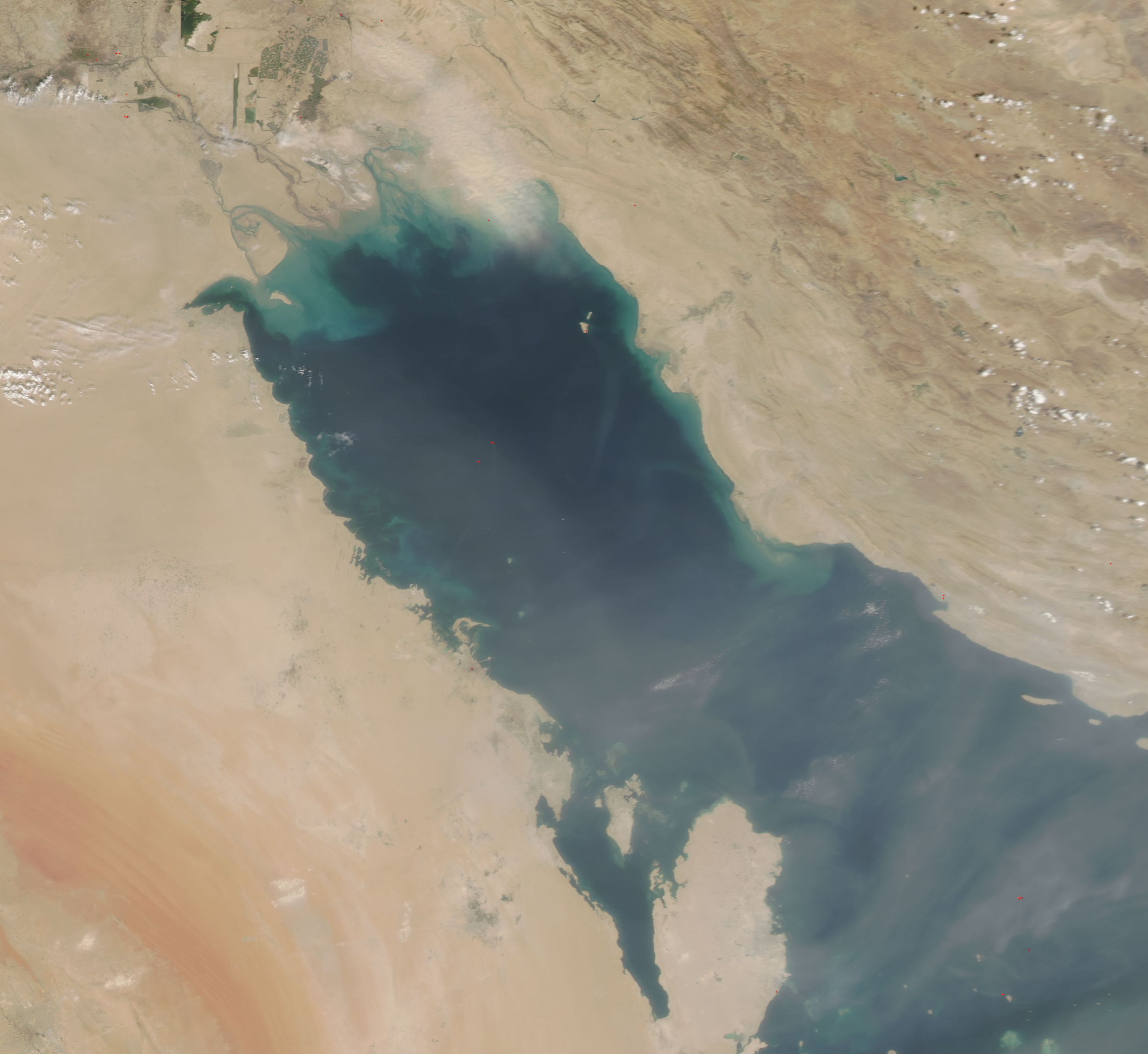

Hasan Hujairi (HH): An island brings with it a peculiar form of seeing the world. Geographically, it may sound like it’s isolated from larger lands, but in reality, the sea that surrounds it brings an infinite chance of someone from somewhere else passing through. The sea, as I have come to know it, is not something that separates people, but rather brings people and their cultures along with them.

Being from Bahrain, a small island that is almost invisible on world maps, allows me to think of where I come from as being a meeting point for others from all over, but also a very unique place with its own indigenous culture and history unlike anywhere else. It is both extraordinary and not at the same time. I think that combination of looking for the ‘extraordinary’ while also strongly believing in the interconnectivity with others carries over to my way of relating to the world, and can be heard within my music.

EN: Your master’s thesis is on the economic history and regional economics of the Gulf region. How have your two fields of study “cross-fertilized” each other?

HH: From my studies in maritime history and economics, I have come to see that the world is far more interconnected than what may appear, and that seas and oceans bring people together rather than cause separation.

It also helped me look at how culture moves from one place to the other, and how the idea of tradition is open to debate and constant reification. Music and the study of its history has also been a way for me to look into understanding dynamics in the social, cultural, and even political realms.

These realizations have sometimes affected my approach to composing, by experimenting with the relation between the performers, audiences, and conductors (if present). It also informs how I make use of sound (as samples or as objects) within a piece of music based on certain sonic phenomena and social structures innate to the world I know.

EN: Several of your pieces are for Kyma and Qanun. Is your choice of Qanun culturally symbolic? Or did you select it for more pragmatic reasons (i.e., you have one and already know how to play it;)

HH: My main instrument for much of the last thirty years has been the oud, which is a fretless lute-like instrument. I only started learning to play qanun over the past year, at around the same time I started with Kyma. I’ve got both instruments available, but what I am trying to achieve with the qanun is to layer different fragments of a maqam (called ajnās, which is the plural form of jins – which are sometimes 3-note, 4-note, or 5-notes in succession that suggest the character of melodic line) across different octaves.

The reason I like this is because my own mistakes and unpolished technique appear in the first layer of bare-bone improvisation, and then when I process some of the audio through Kyma – blemishes and all – and record the resulting sound to use elsewhere, there are always small points of interest that surprise me as I try to figure how/when/where to use the Kyma-processed sounds. I also hope to use this process to dig deeper into the possibilities of Kyma while working in parallel with ideas in music that best reflect my personal interests. I’ve got a number of strange instruments lying around that I still haven’t had the chance to run through Kyma such as the daxophone, theremin, and jahla (percussive clay pots from Bahrain). All in good time.

EN: Wasn’t one of your compositions for Qanun and Kyma recently performed in Vienna?

HH: Yes, on 30 May 2024, my piece “A Home for All Underdogs: Songs of Hope, Failure, and Ambivalence” was played at an event in Vienna’s Echoraum called Sonic Agency – Listening Session XIII.

The program is a project hosted by a Vienna-based platform called Struma+Iodine under its artistic director, booker, and editor-in-chief Shilla Strelka. Shilla had approached me to ask if I would contribute a piece of music between 1:00 – 60:00 minutes in length for their Listening Session series and I very quickly and happily agreed to put something together.

I asked Shilla if the program’s name – Sonic Agency – had anything to do with Brandon LaBelle’s book of the same name. She said that it does – with a few caveats. In fact, Brandon himself had been involved in one of the earlier listening sessions and approved the use of Sonic Agency as a title. However, Shilla strongly felt that with the growing list of contributors, events, references, and projects around Sonic Agency, her curatorial statement has emerged as a manifesto.

EN: Part of that manifesto states that: “Sonic Agency is grounded in the sonic’s ability to introduce the feeling of connectivity, and the possibility of community – a community yet to come”. What is the role of music in introducing a sense of connection and a community yet to come?

HH: From my perspective, I think the collective experience of listening or sharing music/sounds – either at a single moment or over time – creates a bond between people. Perhaps those people also share a particular moral stance on certain global issues, and this act of listening to each other and/or sharing certain music/sonic experiences is a way to collectively empathize, grieve, or perhaps even celebrate. The event of people coming around a sonic act, in essence, could potentially connect people to create a community. This could be one such example of how sound gives agency to a community.

Not only do the circumstances around which we come together as people feel more and more extraordinary, but the sonic experience makes it all the more intense, visceral, personal, and possibly meaningful. It also comes down to a unique shared experience, bringing all those involved somehow together.

EN: Do you believe that music can effect change? In what way(s)?

HH: As music is often part of other phenomena such as rituals, ceremonies, events, protests, demonstrations, and cultural movements, it certainly has in many cases been a part of the bringing of change to different societies. With all that being said, societal change is – in my perhaps naively idealistic view of things – brought about through the collective will of people. I also think that on a more fundamental level, it can affect the space in which it is in, once people engage with it, listen to it, and acknowledge it. All in all, music can effect different forms of change, but it cannot do so without people, who give it meaning or give it agency.

EN: What is a “maverick composer”?

HH: The maverick composer is essentially a categorization of composers who work against convention. Such composers often exist within the intersection of what some may call outlier composers, outsider composers, experimental composers, and even eccentric composers. Moreover, such composers – despite being seen as outsiders to the “tradition” of composition (in the Classical Western Art Music sense) – end up having varying degrees of influence on music composition discourse.

[In 2018], I completed my doctoral thesis on the idea of reorienting maverickism, in which I call for a more inclusive view of “maverick” composers whose musical geneses do not necessarily begin with Classical Western music tradition. For this, I had interviewed Halim El-Dabh, Pauline Oliveros, and Korean gayaegeum master/composer Hwang Byungki.

All these years later, the notion of mavericks and outsiders still fascinates me. The reason behind this fascination in the maverick within a more global outlook would, to me, make the tradition of composition within the scope of Classical Western art music not ‘exceptional’ in the sense that it would exclude all other forms of music traditions from the possibility of innovation and individuality.

There is certainly room for someone from a small island, as in the case of myself, to try to contribute new ideas or concepts into music composition once a more global perspective of possible approaches to composing music is accepted. I find this encouraging and challenging at once, which makes it all the more interesting for me to tackle. Whether I ever succeed in making a contribution to the general discourse on music composition is a whole other debate.

EN: Do you consider yourself an “underdog” or an “outsider”?

HH: I sometimes wonder whether such a way of seeing things could inform my own practice given that I come from a particular part of the world with a very particular culture and history. Now that I think about it, I realize that I have deliberately put myself in situations in which I was an outsider. For instance, when I went to Seoul to study my doctoral degree in music composition, I was asked if I wanted to be part of the Western music department or the Korean music department. I chose to be in the Korean music department because I wanted to make the most of my time there, and to try to work within a music culture that I knew very little about. I thought that this would allow me to reflect on my own background in maqam music from the Middle East.

EN: Could you tell us more about the Sharjah Art Foundation? What have you been doing so far, and what are your longer term goals for the future?

HH: Sharjah Art Foundation is non-profit art foundation based in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. It hosts a broad range of cultural and art events, with some of its core initiatives being the Sharjah Biennial, the annual March Meeting, residencies, production grants, commissions, exhibitions, research, publications and its growing collection. Education and public programming are also a fundamental part of the Foundation’s activities, and one of the key ways of engaging the local communities.

I manage the Music Department, which was established in January 2023 [when I joined] the Foundation. So far, the Music Department has programmed a series of concerts; run educational workshops on field recording, improvisation, and coding; we’ve also collaborated with some music festivals.

For the immediate future, we are planning to expand our activities by setting up an online radio station, hosting music-related talks, publishing albums of performances recorded here, and publishing translations of important music/sound-related texts into Arabic. For example, I’m working on the first Arabic translation of John Cage’s Silence: Lectures and Writings. Although this is a small gesture, I hope that it would introduce a new source of conversation among musicians and composers who only have access to published material in Arabic.

We also have some other very exciting initiatives in the pipelines but it is a little too early for me to disclose them at this point. Ultimately, it is my dream to see Sharjah become one of the important points within the Middle East and North Africa region that makes critical contributions to music and sonic culture.

EN: Musically speaking, how much interchange goes on between artists in in the Gulf region? Are there ever, for example, shared concerts or conferences or exchanges with artists from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, UAE, Kuwait?

HH: Your question on musical interchange happening in the Gulf is a very important one, and it’s something that actually affects how I see things for myself. The notion of the “nation state” in my part of the world, as you can imagine, is a relatively new concept in the grand scheme of things. That being said, borders between what is now known as the Gulf region have always – more or less – been open.

The sea itself was never something that separated people, but rather was one of the key ways in which everyone came together. The same could be said about the desert hinterlands of the Arabian Peninsula – they are in a sense – liquid, in that it carries people and their cultures across.

Music and other forms of culture have been shared and exchanged between the region for potentially thousands of years, and it doesn’t only stop there. There are very clear traces of influence from other parts of the Western region of the Indian Ocean within the music of Bahrain and the Gulf. The presence of music from the eastern coasts of Africa, from southern Iran, and parts of South Asia embedded into the music of Bahrain and the Gulf region is undeniable. This makes the music of the Gulf different from other parts of the Arabic-speaking world.

Today, more modern forms of music in the region may tour around the region, with a great example being the late Ali Bahar and the Al-Ekhwa Band of Bahrain going to Oman only to find a crowd of 50,000 Omanis there to attend the concert. There is also plenty of cultural exchange going between artists from the Gulf region and those from other parts. The influence of music from Egypt, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon – for instance – is undeniable, and we still look at those regions as major cultural hubs for our own understanding of the totality of Arabic music.

EN: What aspect of Kyma would you most like to master over the course of the next year?

HH: What I hope to achieve over the coming year is to slowly build my own set of tools based on a few ideas I’ve been wishing to pursue: those relating to using Kyma as a tool to compose, and those relating to using Kyma as an instrument. I am especially keen on making use of ideas from maqam music theory and making use of techniques to extend instruments such as the qanun or the oud, or ways to manipulate field recordings. My ultimate hope is to find ways to extend compositional/performative techniques related to the music from West Asia and North Africa, along with more vernacular musics from my native Bahrain.

In other words, I’m trying to find a mirror of myself as a composer within Kyma; a mirror that helps me get to know myself better as a composer and as a performing musician.

EN: Hasan, thank you for taking the time to share some of your music, your thoughts, experiences, and plans for the future! It sounds like the monk’s quest is ongoing and will continue for the foreseeable future!

For more about Hasan Hujairi: hasanhujairi.com • www.instagram.com/hasan.hujairi