As part of an on-going series of interviews with artists adapting to and emerging from the disruptions of 2020-22, we had a chance to speak with independent sound artist and photographer Will Klingenmeier to ask him about how he continued his creative work in spite of (or because of?) the restrictions last year, what he is up to now, and some of his hopes and inspirations for the future.

Will is a self-described omnivore of sound and noise, living as a borderline hermit and wanderer in order to focus on developing his unique artistic voice.

Thanks for taking the time to speak with us, Will!

Thank you so much for having me. I’m honored and happy to have the opportunity to talk about my work.

The colors and arrangement of your studio photo seem to capture just how central your studio is in your life (you’ve said that you spend more time there than in in any other place, and I think a lot of us can identify with that). Can you give us a brief description of how you’ve set up your studio workflow and say a bit about how you feel when you’re in the studio and in the flow?

My studio is really sacred ground for me. It’s a special place that I have spent thousands of hours in, as well as making. All of the acoustic treatment, gear racks, speaker stands and shelves I made with my dad over the course of many years. When I’m in the flow it’s like I’m on a tiny planet in my own little world, and it’s immensely satisfying. It’s a source of constant joy and a never-ending project.

At the moment, a lot of what I do is based in Kyma so it is the heart of my studio. I try to perform everything in real-time without editing afterwards; even if it takes longer to get there, it’s more satisfying. I have a few different set-ups including laptops and an old Mac Pro. I have mostly the same content on multiple computers not only for back-ups, but also to make it easier for traveling with a mobile rig. When I can’t avoid using a DAW, I have an old version of Pro Tools on my Mac Pro. Outside of Kyma, I have a handful of microphones, instruments, synthesizers, outboard gear and tape machines that I use. There’s a ton of cabling to the closet turned machine room which looks confusing, but my set-up is actually quite straightforward. Also, I leave all the knick-knacks out so my studio looks like a bricolage, but that way I know where everything is when I need it, and it’s only an arm’s reach away.

During the lockdowns and travel restrictions of spring 2020, you were caught about 7000 miles away from your studio. How did that come about?

I don’t go looking for tough situations, but I always seem to find them. On February 1st, 2020, I left Colorado for Armenia where I was scheduled to volunteer teaching the next generation of noisemakers; two week intensives at four locations around the country, including Artsakh, for a total of two months. I booked a one-way flight so I would be able to travel Armenia and the region, and I had another flight afterward to visit a friend in India, but needless to say that’s not what happened.

When I left the states COVID-19 was around but every day things seemed to stay about the same. For the first month in Armenia things were normal, there wasn’t even a documented case of COVID until March. I made it through two schools and I was at the third when I got a call that the World Health Organization had increased the epidemic to a pandemic. That’s when things changed. A driver came for me and took me back to Yerevan where I was told things were going to change and ultimately go into lockdown. The school said I could stay in their apartment or do whatever I felt I needed to, including going home. I didn’t really know what to do; who did? Throughout my travels I’ve learned not to be reactionary and instead concentrate on options and to realize a working solution. As such, I figured if the virus was going to spread it would be mostly in Yerevan, the biggest city, so I left Yerevan on my own and went to the Little Switzerland of Armenia, Dilijan. It’s an incredibly beautiful place in the mountains and I thought “I’ll lay low here for a few days and plan my next move.”

After five days I decided to go back to Yerevan, and found out that I could have a three bedroom apartment all to myself indefinitely. I thought, “that sounds a lot better than scrambling and traveling 7,000 miles across the world right now”, so I talked with my family and I decided to stay put. I was in that apartment by myself for six months and it was an incredible opportunity to turn inwards. As it turned out, I stayed until one day before my passport stamp expired so I took the experience as far as I possibly could. In hindsight, I don’t think it was ever impossible for me to leave, but I never actually pursued it until I absolutely had to. And I wouldn’t change any of it.

Can you describe how your sound work was modified by your “quarantine” in Armenia? How is it different from the way you normally work in Colorado? Has it changed the way you work now, even after you’ve returned home?

Basically everything I’m doing now has come out of exceedingly difficult situations that I persevered through. Several things happened that I’m aware of and probably even more that I’m unaware of and still digesting. I definitely breached a new threshold of understanding how to use my gear. And I absolutely learned to make the most of what’s on hand—to repurpose things, up-cycle and reimagine. I remember taking inventory of everything I had, laying it all out in front of me and considering what it was capable of doing, the obvious things to start like the various connection ports and so on, then I moved to the more subtle. By doing this I was able to accomplish several things that I didn’t think I could previously based solely on my short-sighted view.

This same awareness and curiosity has stayed with me and I’m really grateful for it. Essentially, it was realizing there’s a lot to be gained in working through discomfort. Moreover, I’ve heard that creativity can really blossom when you’re alone, so maybe that is some of what happened. Not that I held back much before this time, but now I really swing for the fences—I love surreal, far-out, subjective, ambiguous sounds. Creatively speaking, I’m most interested and focussed on doing something that’s meaningful to me, and then I might share it.

Once I returned to Colorado a different level of comfort and convenience came back into my life. Some things were left in Armenia and some things were gained in Colorado. I’ve made it a point to make the most of wherever I am with whatever I have. That’s something I’ve lived by, and now it is a part of me. It is nice to be back in my studio though. I’ve spent more time in this room than any other so I know it intimately. To be sure, I’ve always enjoyed my space and I thrive in solitude so having the situation I did in Armenia really brought out the best in me. Back in the states there are definitely more distractions, so since returning I’ve become even more of a night owl to help mitigate them.

Do you have Armenian roots? Can you explain for your readers what’s going on there right now?

I don’t have Armenian roots, at least none that I know of. That said, I have been told by my Armenian friends that I am Armenian by choice, and I will agree with that. They are a wonderful people and it breaks my heart with what is happening there now. A lot is going on and I don’t claim to understand it all, but there is definitely a humanitarian crisis—thousands dead, thousands of refugees and displaced peoples, and many severely injured people from a 44 day war launched by Azerbaijan. As a result, there are both internal and external problems including on-going hate from the two enemy nations Armenia is sandwiched between. It is a tough time and when I ask my Armenian friends about it they don’t even know how to put it into words. I can see the sadness and worry in their eyes though.

Throughout the pandemic, you’ve maintained connections and collaborations with multiple artists. Please talk about some of those connections, how you established them, how you maintained them, how you continued collaborating (both in terms of technological and human connections).

The first of these collaborations began when I received a ping from one of my good friends and fellow Kyma user Dr. Simon Hutchinson. He said he would like to talk about YouTube. I’d recently started ramping-up my channel (under the name Spectral Evolver) and he was looking to do the same. We discussed the potential for collaboration and cross-promoting our channels. At the time, I was making walking videos around Armenia and we eventually decided to create a glitch art series which used these videos as source material for Simon’s datamoshing. Additionally, we decided to encode the audio for binaural and to use Kyma as a part of the process. We started with short videos up to a minute long with varying content to run some tests, and then started doing longer videos around ten minutes once we figured out the process. We used Google Drive to share the files. It was immensely satisfying and a totally new avenue for me; he is incredibly creative and talented and I was thrilled to be taken along for the datamoshed ride.

Another collaboration during this period was with my long-time friend from college Tim Dickson Jr. He is one of my favorite pianists. Everything he plays is very thoughtful and he has developed this wonderfully minimalist approach. He was going through tough times and wanted to share as much of his creations as possible so I asked him if he wouldn’t mind sending me some of his compositions for me to reimagine. He uploaded about 15 pieces and I used only them and Kyma in creating our album ‘abstractions from underground‘.

‘The Unpronounceables‘ as a trio was yet another collaboration that started during lockdown. Somehow I finagled my way into the group comprised of İlker Işıkyakar and Robert Efroymson, both friends of mine from the Kyma community. At that point, there was still hope for KISS 2020 in Illinois and for us performing as a trio, therefore we needed to start practicing. The only way that was possible at the time was online. As I remember we had a few chats to check-in and say “˜hi’ then we jumped in and started feeling our way forward. The only guideline we ever had was to split the sonic spectrum in thirds, one of us would take the lows, one of us the mids, one of us the highs—that was İlker’s idea I think. However, that quickly disappeared and we all just did what we could. I remember using a crinkled piece of paper as an instrument and opening my window to let the sound of birds and children playing in the courtyard come into the jam. I didn’t have my ganjo yet so I used whatever I could to be expressive, it was really beneficial to work through that. To jam, we used a free application called ‘Jamulus’. Robert made a dedicated server and the three of us would join in once a week and play for 30 minutes or so. Surprisingly the latency wasn’t unbearable. We were doing mostly atonal, nonrhythmic sounds though and I suspect if we needed tight sync it would have been painful.

Finally, despite the lockdown, I was able to continue volunteering with the school once they made the transition to online. While brainstorming with the school on how it would be possible to offer workshops for kids in lockdown at home with seemingly limited resources, I realized I could immediately share what I had just learned: to use whatever you have where you are! The results were spectacular: they created a wonderful variety of sound collages created, recorded and edited mostly through cell phones. I assigned daily exercises to record objects of a certain material, for example, metal, glass, wood etc. I asked them to consider the way the object was brought into vibration by another object. Don’t just bang on it! We also discussed the opportunity to use sound to tell a story even if it’s a highly bizarre, surreal, subjective story. In the end, I learned far more from them than they did from me. I was asking them how they made sounds and I was taking notes. For these classes, we met through Google Hangouts and shared everything on Google Drive.

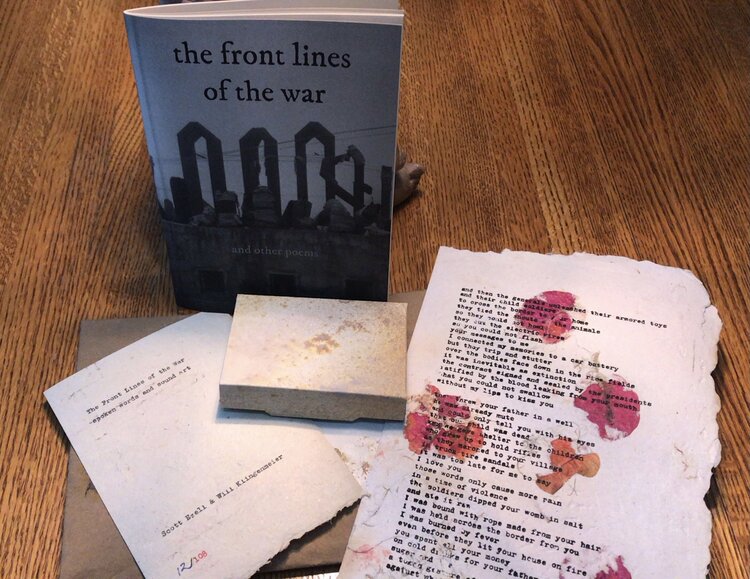

Your recent release, “the front lines of the war,” is the result of another collaboration, this time with Pacific rim poet/multi-disciplinary artist Scott Ezell. Visually, tactilely, sonically and verbally, you and Scott employ multiple senses to express the disintegration and despair of the “shatter zone”. What exactly is a shatter zone?

Shatter Zone has at least a double meaning. It started off in geology to describe randomly cracked and fissured rocks then came to also be used to describe borderlands usually with displaced peoples, so for me, it carries both of those resonances.

The sounds you created for this project are also intentionally distressed and distorted through techniques like bit-crushing, digital encoding artifacts and vocal modulations. Particularly striking is the section that begins “In the shatter zone too long…” whose cracking dripping conveys a miasma of putrescence and disease carried along on a dry wind. Can you describe how you did the vocal processing in this section (and any other techniques you employed in this section that you’d like to share)?

True, there’s a lot of different audio processes happening to make the album sound the way it does including all of the things you’ve mentioned. The piece you’re talking about is called “Shatter Zones” and it came to sound the way it does through Kyma granulation. Scott’s reading of the poem is one take of about 8 minutes and I used a SampleCloud to read through the recording in a few seconds longer than that and used a short grain duration of less than 1 second. What results is a very slightly slower reading, but the pitch of his voice stays the same. It’s just slow enough and granulated enough that we can feel uneasy but not so much that the words aren’t intelligible. It’s super important that we understand what he’s saying so I had to find the line between making an evocative sound and leaving his voice intelligible. I thought there was an obvious correlation to Shatter Zones and granulation which is why I decided to use that technique. The sound around his voice is granular synthesis as well but with long grains of 5 or more seconds. I had this field recording I did on my cell phone of a dwindling campfire, down to the embers, and it always sounded really interesting to me. I brought it into Kyma, replicated it, added some frequency and pan jitter so each iteration wouldn’t sound the same, and used the long grain technique.

What other techniques did you use to “degrade” and “distort” the sound? Did you intentionally choose to distribute the sound component on cassette tape for that reason?

We arrived at putting the sound on a cassette for several reasons. I think a physical element is a really meaningful necessity for music and with the chapbook there was already going to be a physical element so we knew we wanted physical music. These days there’s basically three options: CD, vinyl, cassette — all of which will have a noticeably different sound. We thought about this from the beginning instead of it being an afterthought. Initially, we were thinking vinyl but because of the cost and the length of the sides we realized it probably wasn’t the best solution, if it was even possible. Between a CD and a cassette, this content lends itself to the cassette format more than a CD, not that CD would have been a bad choice. We welcome what the cassette tape might do to the sound—a further opportunity for the medium to influence the art. Besides, over the last year or so I’ve been buying music on cassette—they are really coming back—and they don’t sound nearly as undesireably bad as you might think. In fact, some music sounds best on cassette. I think it’s really cool if an artist considers all the different formats and decides which one is best for the art—like a painter choosing what they will paint on, it matters, it changes the look. When listening to this project on cassette there is a noticeably different experience than listening digitally, and with the exception of one track I think it is all more desirable on the cassette version. As for other techniques for degradation and distortion, I used a lot of cell phone field recordings, there’s a few databent audio files and I recorded out of Kyma into another recorder and during that process a bunch of noise came along. I also have a 1960’s style tone-bender pedal I made a long time ago that’s super special to me, and all of the guitar tones went through that. Then, of course, there’s the stuff inside Kyma which you’ve already hinted at: Bitwise operators, granulation, cross-synthesis and frequency domain haze.

Do you think it’s ironic to use Kyma, a system designed for generating high-quality sound, to intentionally degrade and distort the audio?

Kyma is definitely known for high quality, meticulous sound, but that’s not actually why I got into it, or why I continue to use it. Over the years, I’ve developed and found a way of working that’s meaningful to me and it’s centered around Kyma: real-time creation, no editing, and performing the sound. Kyma thrives in that situation and is extremely stable in both the studio and live use, therefore it’s where I feel really creative and capable of expressing the sound in my head.

One way I think about Kyma is like a musical instrument, say a guitar. What does a guitar sound like? What could it sound like? When does it stop being a guitar sound? Seems to me there’s no end to that and definitely no right or wrong. Kyma is the same way for me. In fact, it never occurred to me that I was making lo-fi sounds in a hi-fi system. I think there’s a sadness when data compression is used for convenience and to miniaturize art, but when it’s used from the onset for a unique sound or look, like we’ve done here, that’s different.

Is this piece about Myanmar? Or is it about “every war” in any place?

Both. The spoken words are specifically based on Scott’s first-person experience of a Myanmar Army offensive against the Shan State Army-North and ethnic minority civilians in Shan State, Myanmar in 2015. Scott was smuggled into Shan State under a tarp in the back of an SUV. The Shan State Suite (side one of the cassette) tells this story. At the same time, the project is expressing a bigger realization as it explores the ways that global systems implicate us all in vectors of destruction and conflict in which “everyone is on the front lines of the war.” (This last sentence is Scott’s words, he said it perfectly for our liner notes, so I’ve just repeated it here.)

Can you offer your listeners any suggestions for remediating action?

It is incredibly difficult not to be lost in despair and discouraged by the things that we, especially Scott, have seen and experienced, but I think the work of art itself is actually meant to be a positive thing. It’s once we fully ignore and disregard things that hope is lost, or rather that we are taking an impossible chance hoping that it “works out for the best.”

I believe we have to make an effort and that effort can come in many forms. This project cracks open the door and offers a start to a conversation, a very difficult, long conversation, but a necessary one, I think. Scott and I have had success bringing this kind of content into different University environments including an ethics of engineering course at the University of Virginia. We shared a piece of art we made and shared our personal experiences and relationships to contested landscapes and marginalized peoples. The response we got from the professors and students suggested there would be on-going consideration for the topic.

Finally, there are lots of good people in the world and lots of human rights organizations seeking to stop violence both before and after it has started, so that’s something encouraging. There is hope and we can start to do better immediately even if only on a very small, personal level. In fact, that’s actually where it all needs to start, I think.

In an ideal world, what would you love to work on for your next project?

An installation of some kind. I really want to do something on a bigger, more immersive, more tactile scale using Kyma and sound as a medium of expression along with some of the visual forms I’ve been getting into. In the meantime I’ll continue to do what I’m doing!

What do you see as the future direction(s) for digital media art and artists? For example, you’ve gone all-in on developing your youtube channel for both educational and artistic purposes, video, and live streaming. How does youtube (and more) figure into your own future plans?

I think we are going to continue to see extremes and new forms of art. Artists, as a whole, always challenge and question which leads to new horizons. Digital media has certainly created many incredible and wonderful on-going opportunities for artists. I see VR/AR getting more and more capable as well as popular. Also, with the advent of everything becoming “˜smart’, new needs have arisen for artists. Like Kyma being used in the design of the Jaguar I-PACE, that kind of stuff. As for my YouTube channel, I have every intention of continuing it. I don’t know exactly what all the content is going to be, but that’s why I put ‘Evolver’ in the name.

As a coda, we strongly recommend that everyone check out the detailed description of ‘the front lines of the war’ on Will Klingenmeier’s website, where you can also place an order for a copy of this beautifully produced, limited-edition chapbook and cassette for yourself or as a gift for a friend.

It’s not an easy work to categorize. It’s an album, it is a video, it’s a chapbook of poetry, yet it’s so much more than that: it is a meticulously crafted artifact which, in its every detail, conveys the degradation, despoilment and degeneration of a “shatter zone”. It arrives at your mailbox in a muddied, distressed envelope with multiple mismatched stamps and a torn, grease-marked address label, like a precious letter somehow secreted out of a war zone, typed on torn and blood/flower stained stationary and reeking of unrelenting grief, wretchedness, and inescapable loss. It deals with many topics that are not easy or comfortable to confront, so be sure to prepare yourself before you start listening.