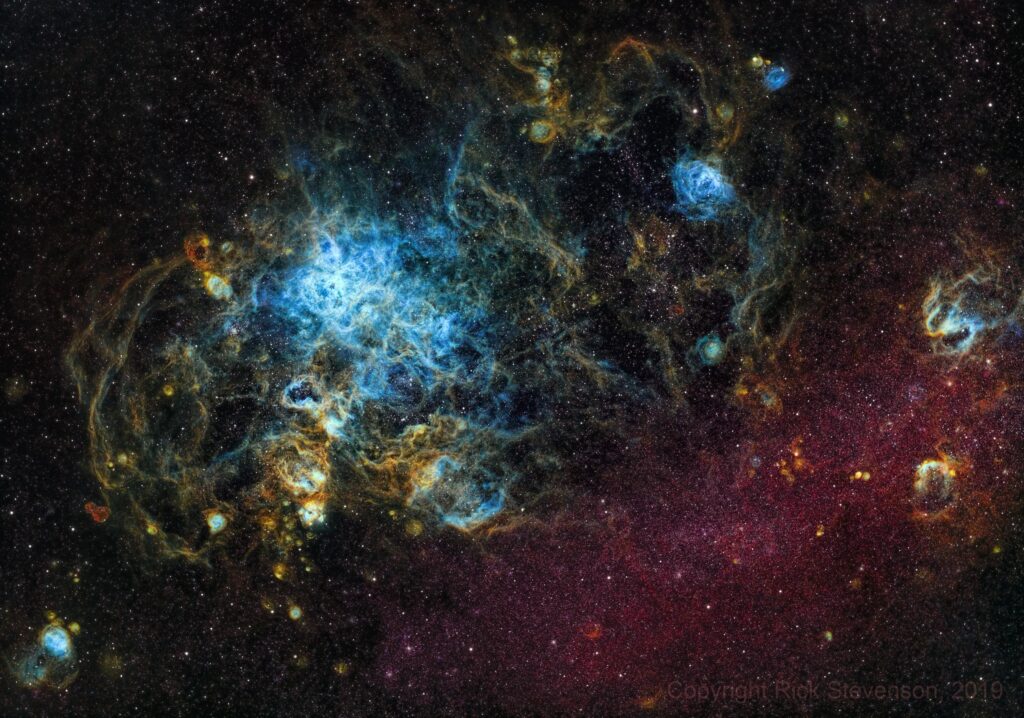

Rick Stevenson is a technology entrepreneur with an impressive track record: he co-founded three successful tech startups and played an instrumental role in the growth of several others. In addition to maintaining a nearly five decade relationship with the University of Queensland’s School of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering as a student, mentor, and industry advisor, Stevenson is also an accomplished astrophotographer, and one of his images was selected as the NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day.

Eighth Nerve [EN] Your “Rungler” patch recently made a big splash on the Kyma Discord Community. Could you give a high-level explanation for how it works?

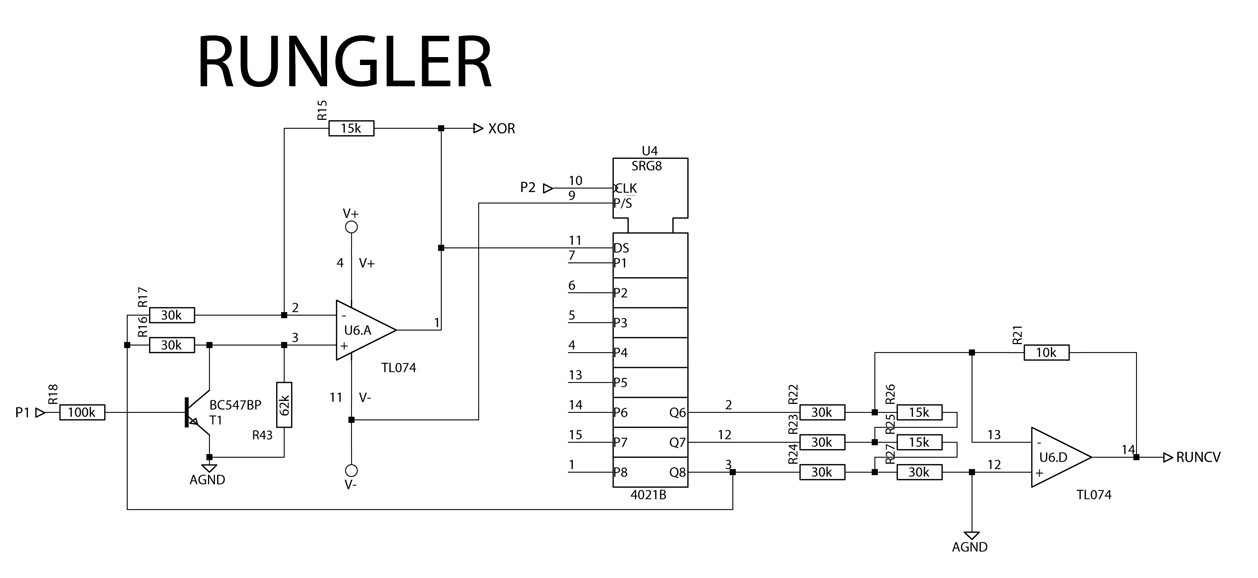

Rick Stevenson [RS]: The Rungler is a hardware component of a couple of instruments, the Benjolin and the Blippoo box, designed by Rob Hordijk. It’s based on an 8-bit shift register driven by two square wave oscillators. One oscillator is the clock for the shift register and the other is sampled to provide the binary data input to the shift register. When the clock signal becomes positive, the data signal is sampled to provide a new binary value. That new bit is pushed into the shift register, the rest of the bits are shuffled along and the oldest bit is discarded.

The value of the Rungler is read out of the shift register by a digital to analog converter. In the simplest version of this (the original Benjolin design) the oldest three bits in the shift register are interpreted as a binary number with a value between 0 and 7.

That part is fairly straightforward. The interesting wrinkle is that the frequency of each oscillator is modulated by the other oscillator and also the value of the Rungler. The result of this clever feedback architecture is that the Rungler exhibits an interesting controlled chaotic behavior. It settles into complex repeating (or almost repeating) patterns. Nudge the parameters and it will head off in a new direction before settling into a different pattern. Despite the simplicity of the design it can generate very interesting and intricate “melodies” and rhythms.

NOTE: Rick shared his Rungler Sound in the Kyma Community Library!

Artist/animator Rio Roye helped Rick test the Rungler Sound and came up with a pretty astounding range of sonic results!

[EN]: What is your music background? Is it something you’ve been interested in since childhood? Or a more recent development?

[RS]: I didn’t learn an instrument as a child. I’m not sure why. We had a piano in the house and my mother played. At high school I taught myself to play guitar and bass and I kept that up for a couple of years at University but eventually gave up due to lack of time and motivation. Quite a few years later when work demands became manageable and our children were semi-independent, I took up guitar again and started tinkering with valve amp building. These days I’m learning Touch Guitar and tinkering with synths and computer music. I spent some time learning Max and Supercollider then decided to take the plunge into Kyma.

[EN]: What were the best parts of your “new user experience” with Kyma?

[RS]: I really liked the wide range of sounds in the library. It’s great to be able to find an interesting sound, play with it, and then dig inside and try to figure out how it works.

I also appreciated the power of individual sounds coupled with the expressiveness of Capytalk. I spent quite a bit of time learning Max and moving to Kyma was a bit like switching from assembler to a high level language.

[EN]: I think you might be the first astrophotographer I’ve ever met! Could you please introduce us (as total novices) to the equipment and software that you use to capture & process images like these…

[RS]: You can do astrophotography with a digital camera and conventional lens. A tripod is sufficient for nightscapes but you need some sort of simple tracking mount to do longer exposures. At the other end of the spectrum (haha) are telescopes, cameras and mounts specifically designed for astrophotography. The telescopes range from small refractors (with lenses) to large catadioptric scopes combining a large mirror (500mm in diameter or even more) with specialized glass optics.

Cameras consist of a CCD or CMOS sensor in a chamber protected from moisture, thermally bonded to a multistage Peltier cooler. Noise is the enemy of faint signals so it is not uncommon to cool the sensor to 30C or more below ambient temperature. The cameras are usually monochromatic and attached to a wheel containing filters. Mounts for astrophotography are solid, high precision devices that can throw around a heavy load and also track the movement of the sky with great accuracy. Summary: there’s lots of fancy hardware used for amateur astrophotography, ranging from relatively affordable to the price of a nice house!

On the software side, the main components are capture software which runs the mount, filterwheel and the camera(s), and processing software which turns the raw data into an image. Normal procedure is to take many exposures of a deep sky object from seconds to many minutes long and “stack” them to increase the signal to noise ratio. We also take a few different types of calibration images that are used to remove artifacts and nonlinearities from the camera sensor and optical train. Processing the raw data can be an involved process and is something of an art in itself. There are quite a few software packages and religious wars between their proponents are not uncommon.

[EN]: Speaking of software packages, what is PixInsight?

[RS]: PixInsight is the image processing and analysis software that I use. It has been developed by a small team of astronomers and software engineers based in Spain. It has a somewhat unfair reputation for being complicated and difficult to use. This is partly down to a GUI which is the same on Windows, Mac and Linux (but not native to any of them) and partly because it includes a wide range of different tools and the philosophy of the developers is to expose all of the useful parameters. When I started doing astrophotography I tried a few different software packages and PixInsight was the one that produced the best results for me. Some of the other commonly used packages hide a lot of the ugly details and offer a more guided experience which suits some types of imagers better. A more recent development is the use of machine learning in astronomical processing to do things like noise reduction and sharpening. I haven’t quite decided how I feel about that yet.

I think there are some interesting parallels between PixInsight and Kyma. Apart from the cross platform problem, both have to maintain that careful balance that offers a complex, highly technical set of features in a way that can satisfy the gamut of users from casual to expert.

[EN]: Do you have your own telescope? Do you visit telescopes in other parts of the world?

I have a few telescopes. Unfortunately, I live in the city and the light pollution prevents me from doing much data collection from home. When I get the opportunity I have a few favorite locations not too far away where I can set up under dark skies. Apart from dark skies, a steady atmosphere is important for high resolution imaging. This is called the “seeing” and it’s usually not that great around here.

For several years I have been a member of a few small teams with automated telescopes in remote locations. That solves a lot of problems apart from fixing things when they go wrong! My first experience was at Sierra Remote Observatory near Yosemite in California. I also shared a scope with some friends in New Mexico and now I’m using one in the Atacama Desert in Chile. The skies in the Atacama are very dark and the seeing is amazing! I haven’t ever visited any of the sites but I did catch up with some team mates on a couple of business trips.

[EN]: Does your camera give you access to data files? From some of the caption descriptions, it sounds like your camera has sensors for “non-visible” regions of the spectrum, is that true?

[RS]: The local and the remote scopes all deliver the raw image and calibration data in an image format called “FITS” which is basically a header followed by 2D arrays of data values. A single image will almost always be produced from very many individual sub-exposures. The normal process is to calibrate and stack the data for each filter before combining the stacks to produce a color image.

The camera sensors will usually detect some UV and near-infrared as well as visible light, but they aren’t commonly used in ground-based imaging. I use red, green and blue filters for true color imaging, or I image in narrowband. Narrowband uses filters that pass very narrow frequency ranges corresponding to the emissions from specific ionized elements, usually Hydrogen alpha (a reddish color), Oxygen III (greenish blue) and Sulphur II (a different reddish color). Narrowband has the advantage of working even in light-polluted skies (and to some extent rejecting moonlight) and can show details in the structure of astronomical objects not visible in RGB images. The downside is that you need very long exposure times and narrowband images are false color. Many of the Hubble images you’ve undoubtedly seen are false color images using the SHO palette (red is Sulphur II, green is Hydrogen alpha and blue is Oxygen III).

[EN]: What is your connection with the Astronomical Association of Queensland?

[RS]: I have been a member of the AAQ for well over a decade. From 2013 to 2023 I was the director of the Astrophotography section. I helped members learn how to do astrophotography, organized annual astrophotography competitions and curated images for the club calendar.

[EN]: Have you ever seen a platypus in real life?

[RS]: Several times at zoos. Only a handful of times in the wild. They are mostly nocturnal and also very shy!

[EN]: In New Mexico (where I grew up), we all learned a song in elementary school with the lyrics: “Kookaburra sits in the old gum tree, merry merry king of the bush is he, Laugh Kookaburra, laugh Kookaburra, gay your life must be”. Is it a pseudo-Australian song invented for American kids or did you learn it in Australia too?

[RS]: I don’t know the origin but we have the same song. I have a toddler grandson who sings it! We have Kookaburras in the bushland behind our house that start doing their group calls around 3 or 4am.

Speaking of the Kookaburra song there was a story about it in the news a few years ago when the people who own the rights to the song won a plagiarism lawsuit against the band, Men at Work.

Listen for the Kookaburra song in the flute riff!

[EN]: What was the best part about growing up in Australia that those of us growing up in other parts of the world missed out on?

[RS]: Vegemite, perhaps? 🙂

The area around Brisbane in South-East Queensland has a lot going for it. The climate is pleasant and mild (except for some hot and humid days in summer). There are great beaches within an hour or so as well as forested areas for hiking. The educational and health systems are good, even the public / “free” parts (true in most of the major centres in Australia). Brisbane is large enough to have some culture and work opportunities without being too busy and fast-paced. It’s pretty good, but not perfect.

[EN]: What was your favorite course to teach at the School of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, University of Queensland St Lucia?

[RS]: I was an Adjunct Professor at UQ ITEE for 21 years but I didn’t teach any courses. I acted as an industry advisor, was involved in bids to set up research centers in embedded systems and security, and I hired a lot of their graduates!

[EN]: Do you have a “favorite” programming language or family of languages?

[RS]: I rather liked Simula 67 though I only used it for one (grad student) project. I think it was one of the first OO languages if not the first. Most of my work programming experience was in assembler on microprocessors and C on micro and minicomputers. I was very comfortable in C but wouldn’t say I loved it. These days I quite like the Lisp family of languages.

[EN]: Are you one of the founders of OpenGear? In that role, do you do a lot of international travel to the company’s other offices?

[RS]: I was one of the founders and worked in a few roles up until Opengear was acquired in late 2019. Having stayed on after acquisitions in a couple of previous lives I was pleased that the new owners didn’t want me to hang around and I exited just in time for COVID. While at Opengear and in previous startups I made regular business trips, mostly to North America but also the UK and Europe and occasional trips to South-East Asia.

[EN]: What do you identify as the top three “open problems” or “grand challenges” in technology right now?

[RS]: In no particular order and not claiming to have any deep insights…

- Achieving AGI [artificial general intelligence] is still an open problem and one that, in my opinion, is not going to get solved as quickly as a lot of people think. Maybe that’s a good thing?

- I spent about a decade working on computer security products starting in the early 2000s and despite a lot of money and effort spent on band-aid solutions, things have only become worse since then. Fixing our whack-a-mole computer security model is certainly a grand challenge, not helped by the incentives that security vendors have to protect their recurring revenues. The recent outage caused by the CrowdStrike security agent crashing Microsoft computers demonstrates the fragility of our current approach.

- The ability to create practical quantum computers still seems a bit of a reach though I hear that Wassenaar Arrangement countries are all quietly introducing export controls on quantum computers. Perhaps they know something I don’t.

[EN]: What’s next on the horizon for you? What Kyma project(s) are you planning to tackle next?

[RS]: I have a long list of potential projects but I think the next two I’ll tackle are some baby steps into sonification of astronomical data (thanks for the encouragement) and a Blippoo Box – another of Rob Hordijk’s chaotic generative synths.

[EN]: What are you most looking forward to learning about Kyma over the next year?

[RS]: There are many areas of Kyma that I have only dabbled in and even more that I haven’t touched at all. I’d like to get a lot more fluent with Smalltalk and Capytalk, do some projects with the Spectral and Morphing sounds and also plumb the mysteries (to me) of the Timeline and Multigrid. That should keep me busy for a while!

[EN]: Outside of Kyma, what would you most like to learn more about in the coming year?

[RS]: I have a couple of relatively new synths, a Synclavier Regen and a Buchla Easel, that I would like to spend a lot more time learning my way around. I also want to keep progressing with my Touch Guitar studies.

[EN]: Rick, thank you for the thought-provoking discussion! Can people get in touch with you on the Kyma Discord if they have questions, feedback, or proposals for collaboration?

[RS]: Yes!