Kyma 7.43f5 is here, and it’s packed with new features for customizing your Kyma environment and enhancements to optimize your realtime sound design experience.

Highlights:

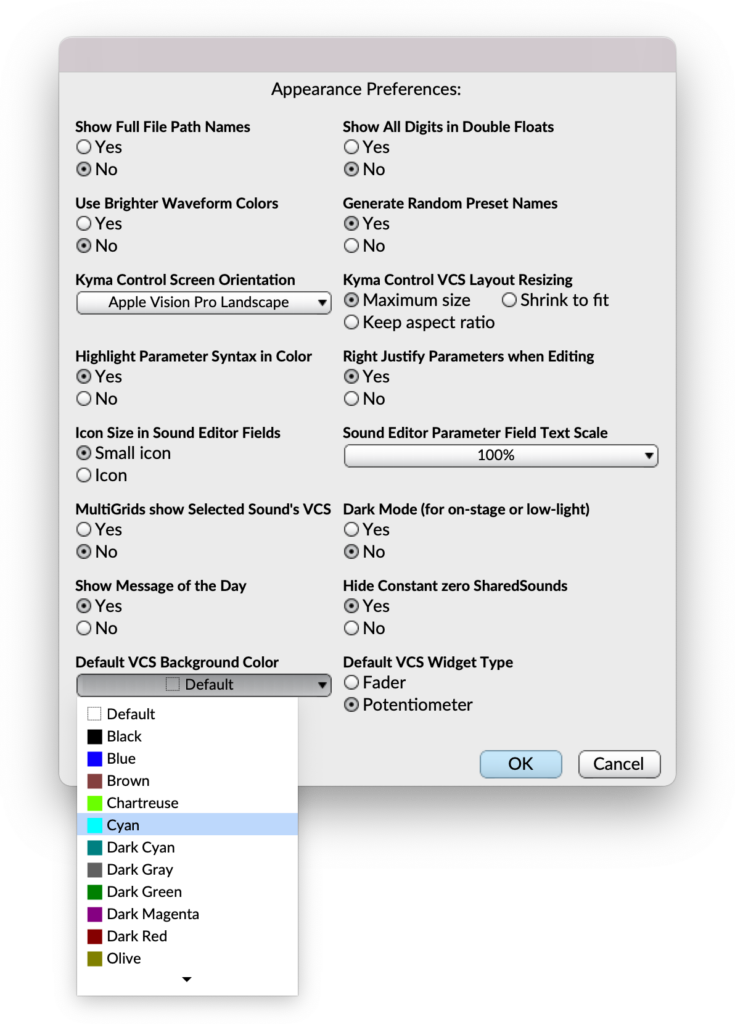

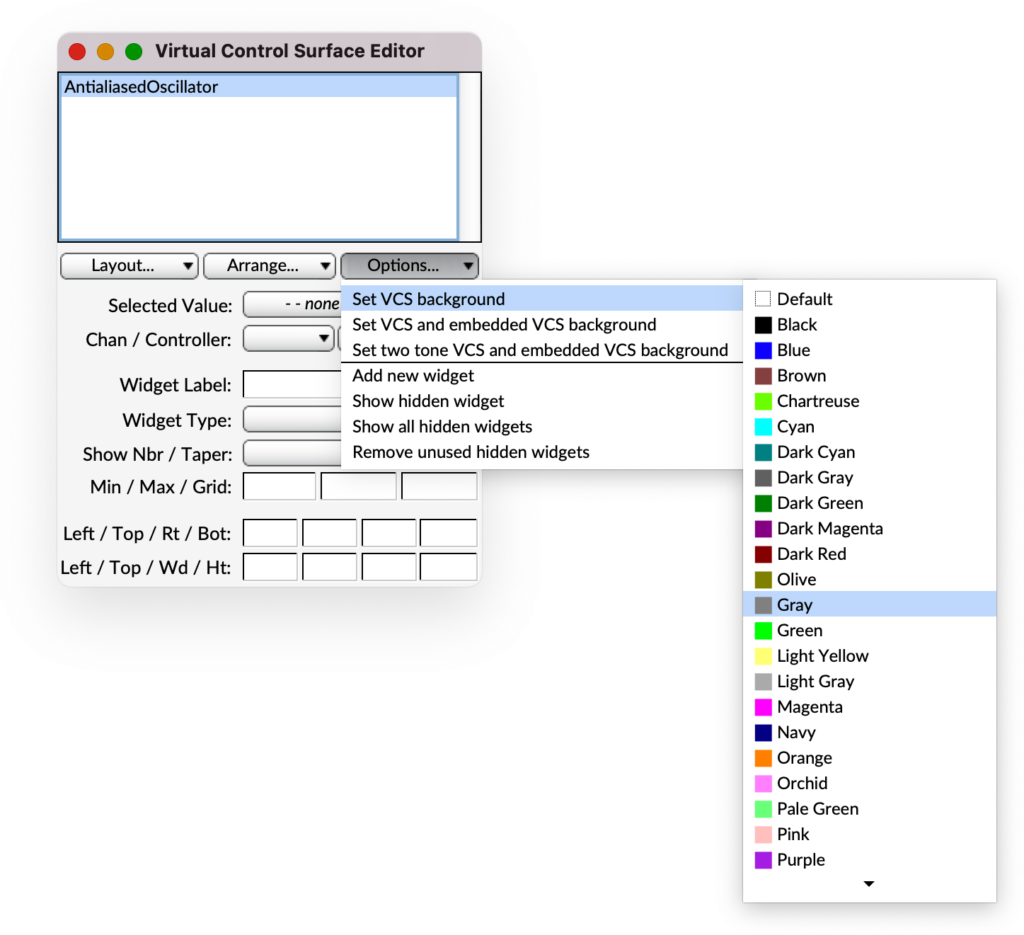

• Personalize your Workspace: Choose from a variety of default background colors and widgets for your Virtual Control Surface to create a more personalized and comfortable work environment.

• Enhanced Color Selection: Color swatches guide your selection process, making it easier to find the perfect color combinations

• Smoother Performance: Enjoy smoother and more responsive screen updates.

New Features:

• Capytalk for Non-Linear Lookups: Perform complex non-linear lookups into arrays of changing EventValues, unlocking new possibilities for interactive control over Kyma Sound parameters

• Improved Interpolation for Capytalk intoXArray:yArray: Continuously variable interpolation methods offer greater flexibility and control over how values are mapped between points — from immediate, to linear, to piecewise spline interpolation

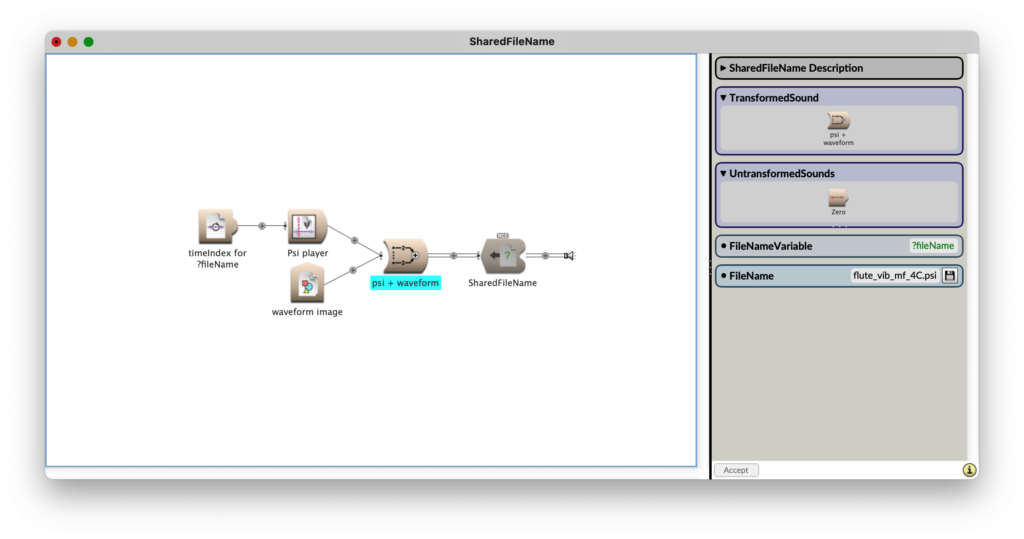

• Shared Files: Manage file references within your Kyma Sounds using SharedFileName and SharedFileNames. These new Sounds streamline your workflow by replacing all occurrences of file variables with your chosen file selections.

Additional Enhancements:

• Improved InputOutputCharacteristic for Pacamara Ristretto: This Sound has been rewritten for enhanced efficiency, accuracy, and piecewise spline interpolation.

• Inspiring new Samples and Images: Spark your creativity with a fresh set of samples and images provided by composer/performer Andrea Young and astrophotographer/sound designer Rick Stevenson.

…and more!

Download the update today to unlock the full potential of your Kyma-Pacamara sound design environment! Available free from the Help menu in Kyma.

The flow state (otherwise known as “in the zone”) is what every real-time performer seeks.

The flow state (otherwise known as “in the zone”) is what every real-time performer seeks.