Is John Mantegna using Kyma Control at White Sands? And what does he mean by this quote?

“I think the VP is awesome!”

Kyma update features enhancements to interface

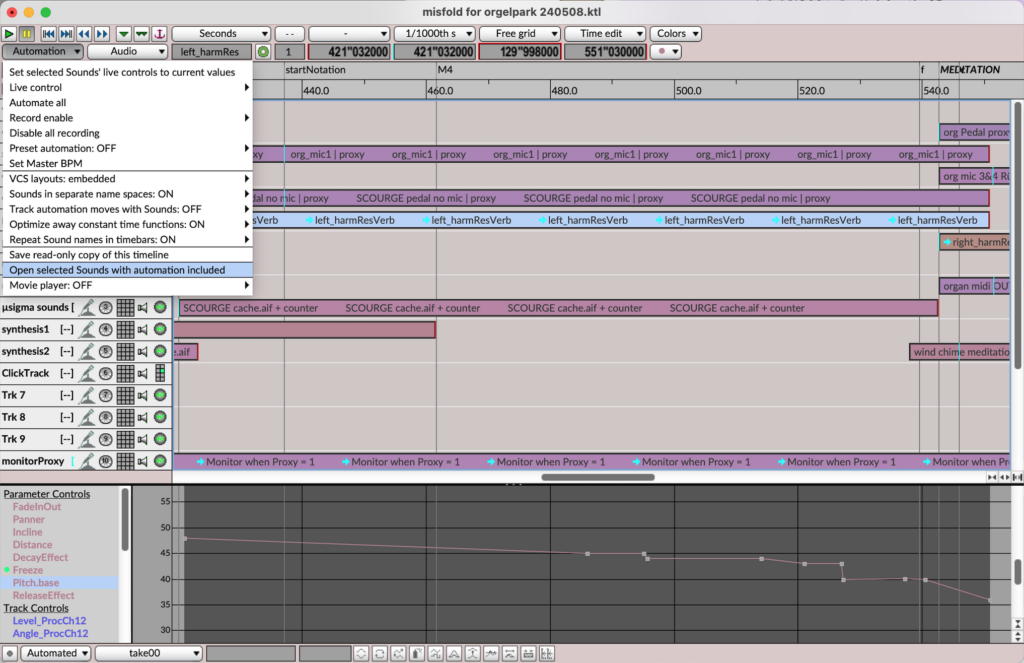

The newest update to Kyma (7.42f5) features improvements to the interface and several handy new features including:

-

- For more accurate placement of Sounds during drag-and-drop, the cursor changes to a cross-hairs with transparent center plus corners during dragging.

- Enhanced syntax coloring matches the colors of corresponding pairs of open/close brackets and parentheses.

-

- Cleaner signal flow diagrams, thanks to an option to hide Constant Zero shared Sounds in Replicators (Edit menu > Settings > Appearance)

- New option to open a Sound with a MapEventValues for mapping the parameter automation functions from the bottom of the Timeline, so you can hear the Sound on its own with the same settings it has in the context of the Timeline with those parameters automated.

- There’s a new keyboard shortcut for unlocking the VCS for editing. Cmd+T (mnemonic TRANSFORM VCS or Turn-on the editor) that is equivalent to Action menu > Edit VCS layout

As well as multiple other fixes and enhancement requests from the Kyma community (thank you for your reports and feedback!)

The new update is free, and you can download it from the Help menu in Kyma.

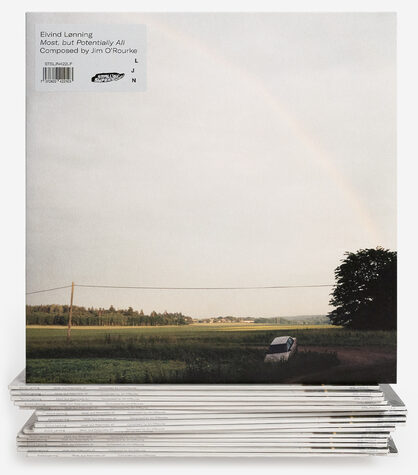

Most, but potentially all Composed by Jim O’Rourke

Longtime collaborators trumpeter Eivind Lønning and composer Jim O’Rourke have just released an intoxicating new album on Boomkat: Most, but potentially all Composed by Jim O’Rourke.

Lønning provides exquisite acoustic trumpet sounds and O’Rourke’s Kyma transformations, described by Boomkat as “often gentle and illusory, and sometimes utterly lacerating – lift the sounds into completely new territory.”

The entire album was composed, mixed and mastered by O’Rourke and is based solely on material from Lønning’s virtuosic performance.

In the words of the Boomkat reviewer, it’s a “piece that shifts the dial on contemporary experimental music; dizzyingly complex but never showy, it’s the kind of record you can spin repeatedly and hear something different each time… as a progression of electro-acoustic compositional techniques, it draws a deep trench in the sand, setting a new standard.”

Lønning is touring with the material starting with a 29 May 29 2024 concert at the Edvard Munch museum.

Data sonification for scientific exploration & discovery

Data sonification, often used for outreach, education and accessibility, is also an effective tool for scientific exploration and discovery!

Working from the Lindorff-Larsen et al Science (2011) atomic-level molecular dynamics simulation of multiple folding and unfolding events in the WW domain, we heard (and analytically confirmed) correlations between hydrogen bond dynamics and the speed of a protein (un)folding transition.

The results were published this week in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), vol. 121 no. 22, 28 May 2024: “Hydrogen bonding heterogeneity correlates with protein folding transition state passage time as revealed by data sonification”

Congratulations to everyone in the Biophysics Sonification Group:

Carla Scaletti (1), Premila P. Samuel Russell (2), Kurt J. Hebel (1), Meredith M. Rickard (2), Mayank Boob (2), Franz Danksagmüller (9), Stephen A. Taylor (7), Taras V. Pogorelov (2,3,4,5,6), and Martin Gruebele (2,3,5,8)

(1) Symbolic Sound Corporation, Champaign, IL 61820, United States;

(2) Department of Chemistry, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, IL 61801, United States;

(3) Center for Biophysics and Quantitative Biology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, IL 61801, United States;

(4) School of Chemical Sciences, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, IL 61801, United States;

(5) Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, IL 61801, United States;

(6) National Center for Supercomputer Applications, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, IL 61801, United States;

(7) School of Music, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, IL 61801, United States;

(8) Department of Physics, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, IL 61801, United States;

(9) Musikhochschule Lübeck, 23552 Lübeck, Germany

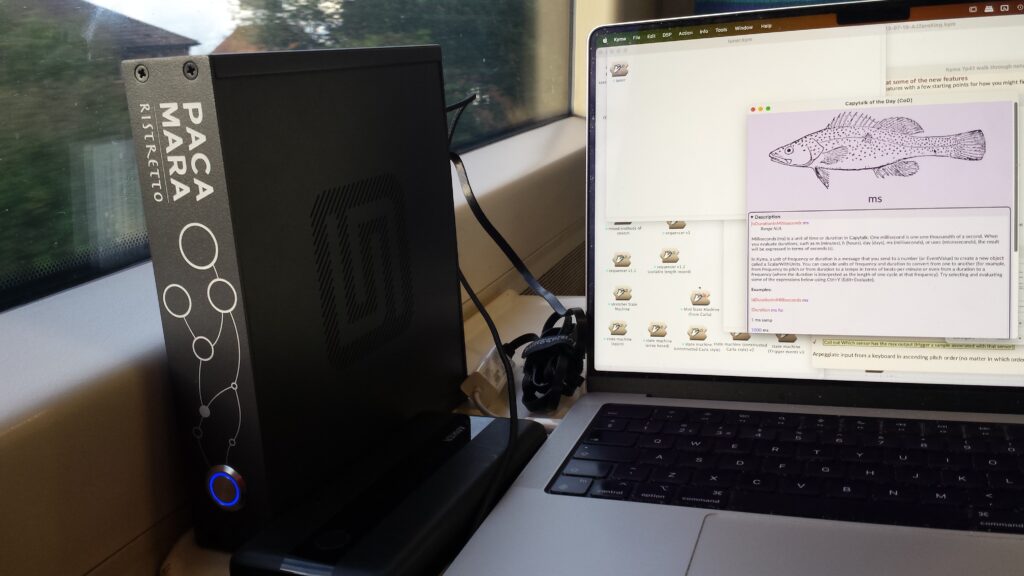

Kyma consultant Alan Jackson’s studio

Musician and Kyma consultant, Alan Jackson, known for his work with Phaze UK on the Witcher soundtrack, has wired his studio with an eye toward flexibility, making it easy for him to choose from among multiple sources, outputs, and controllers, and to detach a small mobile setup so he can visit clients in person and even continue working in Kyma during the train ride to and from this clients’ studios.

In his studio, his Pacamara Ristretto has a USB connection to the laptop and is also wired with quad analog in / out to the mixer. That way, Jackson can choose on a whim whether to route the Ristretto as an aggregate device through the DAW or do everything as analog audio through the mixer. Two additional speakers (not shown) are at the back of the studio and his studio is wired for quad by default.

The Faderfox UC4 is a cute and flexible MIDI controller plugged into the back of the Pacamara, ready at a moment’s notice to control the VCS, and a small Wacom tablet is plugged in and stashed to the left of the screen for controlling Kyma.

Jackson leaves his Pacamara on top so he can easily disconnect 5 cables from the back and run out the door with it… which leads to his “mobile” setup.

Jackson’s travel setup is organized as a kit-within-a-kit.

The red, inner kit, is what he grabs if he just needs a minimal battery-powered Kyma setup, e.g., for developing stuff on the train, which includes:

- a PD battery (good for about 3 hours when used with a MOTU Ultralite, longer with headphones)

- a pair of tiny Sennheiser IE4 headphones

- a couple of USB cables, and an Ethernet cable

- a 4 in / 4 out bus-powered Zoom interface

- mains power for the Pacamara

- more USB cables

- a PD power adaptor cable, so he can run the MOTU Ultralite off the same battery as the Pacamara

- a clip-on mic

- the WiFi aerial

If you have any upcoming sound design projects you’d like to discuss, visit Alan’s Speakers on Strings website.

When not solving challenges for game and film sound designers, Alan performs his own music for live electronics.

Zero mass reflections at the EICAS Museum

Sound artist Roland Kuit has three sonic installations currently showing at the EICAS Museum Deventer in the Netherlands, all of which use Kyma.

ZERO = Language – Roland Kuit

Nonversation – Roland Kuit, 2024

Two video screens, each with an alphabetical circle. The circles are traversed by Brownian Walks to generate random letters. The letters are named on one side by Roland Kuit and on the other by artist Karin Schomaker. The found meaning lies in the process of discovering random synchronicity.

Mass – Roland Kuit, 2024

A laboratory with six thousand table tennis balls representing people using social media. Ideas that are pushed through with good or bad intentions in a chaotic world. Visible in this field, is the movement of this chaos. Chaos will always move towards equilibrium. That is looking for a balance and fixing yourself there. This balance may be called polarization. Fixed, and not free. Then it is up to the attendant or spectator to direct the fan(s) differently as new input of an idea to restart this chaos, until a new balance is found. This repeats as long as there are people willing to share ideas.

Reflections with textless paper – Roland Kuit, 2024

Because people disappear into the bubbles of social media, the news fades. The algorithms of the Internet do everything they can to keep people in the bubble. In this installation one sees the newspaper texts fading, newspapers crumpled and thrown away, torn. Cramming memories of something new. This installation shows that a different reality emerges. The fragility of the works on the wall symbolize our democracy and the rule of law. Values on which one could build. These values, seem to fade, lie on the ground. As a reminder, one hears the crackling, crumpling, crumpling and tearing from the loudspeakers on the wall. Like an infinite loop of fading into something that was once reality.

From 4 February to 26 May

Museum EICAS

Nieuwe Markt 23

7411 PB Deventer

AWAY in Dublin

Anne La Berge and Diamanda La Berge Dramm performed “AWAY” as part of New Music Dublin in a late-evening concert on the Diatribe Stage in what was described as an “impossible, rousing mix of electro and songs”.

AWAY draws together Diamanda’s practice as one of the foremost contemporary violinists, singers and composers of her generation with Anne’s passion for the extremes in composed and improvised music, and her work as a multimedia performer.

Friday 26 April 2024, 10.00pm

Venue: Kevin Barry Recital Room, NCH

Anne La Berge, flute / electronics / voice

Diamanda La Berge Dramm, violin / voice

Acrylic Sounds

Giuseppe Dante Tamborrino asks:

Why is it that a Picasso painting can be widely known and understood by everyone, while sound abstractions are still considered academic and incomprehensible?

Tamborrino’s answer to that question, Acrylic Sounds, was born in January 2024 in the Laterza province of Taranto – Puglia – Italy in the garage of the professor and composer of electro-acoustic music.

Between 2019-2021 (in the period of COVID-19), Tamborrino created a series of abstract paintings using some of the same algorithms he has been using to generate CSound scores for the past 10 years. His idea was to bring his students closer to the concept of sound abstraction by applying the same principles of abstraction to paintings as to musical scores.

Tamborrino does not call himself a painter and has always argued that painting is painting, sound is sound, and sculpture is sculpture; each has a different role, but sometimes they use the same concepts.

While waiting for his score generation algorithms to compile, Tamborrino engaged in creative outbursts with a sponge and a brush as he drew lines or experimented with random color transformations obtained by sponging, likening it to techniques of sound morphing.

Taking these 60 semi/casual paintings as inspiration, he then realized them as Sounds in Kyma. For each painting, he created a formal pre-design and customized Smalltalk scripts to get closer to the meaning of the picture under analysis.

For the sonorisation of the painting “La Sinusoide” he used a Capytalk expression that allows you to control the formants of a filter and the index of the formants with the Dice tool of the Kyma Virtual Control Surface (VCS), generating several layers gradually and quickly with the “smooth” Capytalk function.

He also used the Kyma RE Analysis Tool for the generation of a Resonator-Exciter filter, creating transformations of the classic sine wave with the human voice.

He used a real melismatic choir, because the painting represents a talking machine…

For “Le Radio”, Tamborrino tried to simulate the search for the right radio station, transforming songs between them. To do this he reiterated several times sounds and music produced by a group of songs in the same family using a simple “ring modulator” to suggest AM radio and used a Capytalk expression to emulate the gradual spectral transformation effect of switching radio stations combined with random gestures to simulate the classic noise between the station and the music. Finally, he used granular synthesis to create glitch rhythmic transitions and figurations and combined selected abstract material as multiple tracks of a Timeline.

“The Mask of the Seagulls” was inspired by the observation of an elderly man annoyed by the anti-COVID mask and some seagulls that repeatedly circled around him, chanting and emitting verses as if nature were making fun of him.

To express the annoyance of the man, Tamborrino simply recorded his own breath recorded through a mask.

For the creation of this syneathesia, Tamborrino emulated the behavior of cheerful and playful seagulls, with a script for the management of the density, frequency, and duration of the grains of granular synthesis; in exponential mode with decelerations and accelerations and friction functions for physics-based controls and swarming.

All of these layers were then assembled in a multi-track Timeline.

Tamborrino plans to publish the work as a book of paintings with QR codes for listening and will exhibit the work as paintings paired with performances on an acousmonium.

Some of Tamborrino’s recent work can be heard at the upcoming New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival, and he has recently released a new album under the Stradivarius Records label.

Mei-ling Lee’s Sonic Horizons

Music professor Mei-ling Lee was recently featured in the Haverford College blog highlighting her new course offering: “Electronic Music Evolution: From Foundational Basics to Sonic Horizons”, a course that provides students with an in-depth introduction to the history, theory, and practical application of electronic music from the telharmonium to present-day interactive live performances driven by cutting-edge technologies. Along the way, her students also cultivate essential critical listening skills, vital for both music creation and analysis.

In addition to introducing new courses this year, Dr. Lee also presented her paper “Exploring Data-Driven Instruments in Contemporary Music Composition” at the 2024 Society for Electro-Acoustic Music in the United States (SEAMUS) National Conference, held at the Louisiana State University Digital Media Center on 5 April 2024, and published as a digital proceeding through the LSU Scholarly Repository. This paper explores connections between data-driven instruments and traditional musical instruments and was also presented at the Workshop on Computer Music and Audio Technology (WOCMAT) National Conference in Taiwan in December 2023.

Lee’s electronic music composition “Summoner” was selected for performance at the MOXSonic conference in Missouri on 16 March 2024 and the New York City Electronic Music Conference (NYCEMF) in June 2024. Created using the Kyma sound synthesis language, Max software, and the Leap Motion Controller, it explores the concept of storytelling through the sounds of animals in nature.

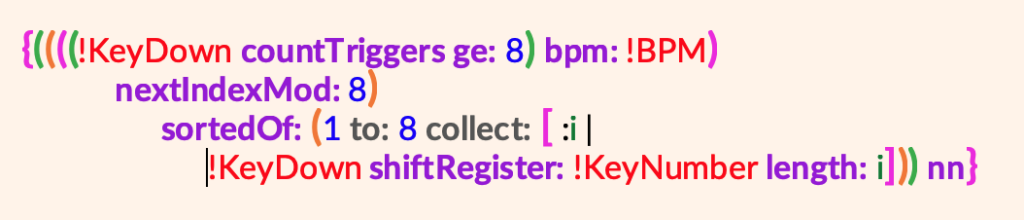

Danksagmüller at the Orgelpark

Virtuoso organist / composer / live electronics performer, Franz Danksagmüller is presenting an afternoon workshop followed by an evening concert of new works for “hyper-organ” and Kyma electronics at the Orgelpark in Amsterdam, Friday 7 June 2024, as part of the 2024 International Orgelpark Symposium on the theme of ‘interfaces’ (in the broadest sense of the word).

Virtuoso organist / composer / live electronics performer, Franz Danksagmüller is presenting an afternoon workshop followed by an evening concert of new works for “hyper-organ” and Kyma electronics at the Orgelpark in Amsterdam, Friday 7 June 2024, as part of the 2024 International Orgelpark Symposium on the theme of ‘interfaces’ (in the broadest sense of the word).

In his symposium, “New Music, Traditional Rituals“, Danksagmüller wrestles with the question of how new music might play a role in liturgy and religious rituals. While the development of the so-called hyper-organ reveals the strong secular roots of the pipe organ, which, after all, spent the first 15 centuries of its life outside the church, the pipe organ has also been significantly formed by its six centuries within the church, a church which inspired organ builders and organists to create the magnificent instruments that remain an important part of Europe’s patrimony today.

Is there a role for new music in the church? In their pursuit of “truth” do scientists and theologians share any common ground? Danksagmüller does not shy away from the “big questions”!